Deciphering North Carolina’s Dialects With Help From a Linguistics Professor

When it comes to understanding the variety of dialects and vernacular of North Carolina, this scholar is no dit dot.

Paul Brown |When it comes to understanding the variety of dialects and vernacular of North Carolina, this scholar is no dit dot.

Walt Wolfram, distinguished professor at North Carolina State University, has loved language since childhood.

“My parents were immigrants who didn’t speak English, so I had a natural curiosity related to language,” Wolfram says. He studied linguistics as a young adult, intending to translate the Bible as a foreign missionary. But circumstances steered him into academia instead.

After doing research and teaching in Washington, D.C., for two decades, Wolfram joined NC State’s faculty in 1992, unaware of how the state would shape his career.

“When I came here 28 years ago,” he says, “a lot of North Carolina hadn’t really been studied in terms of its linguistic diversity.”

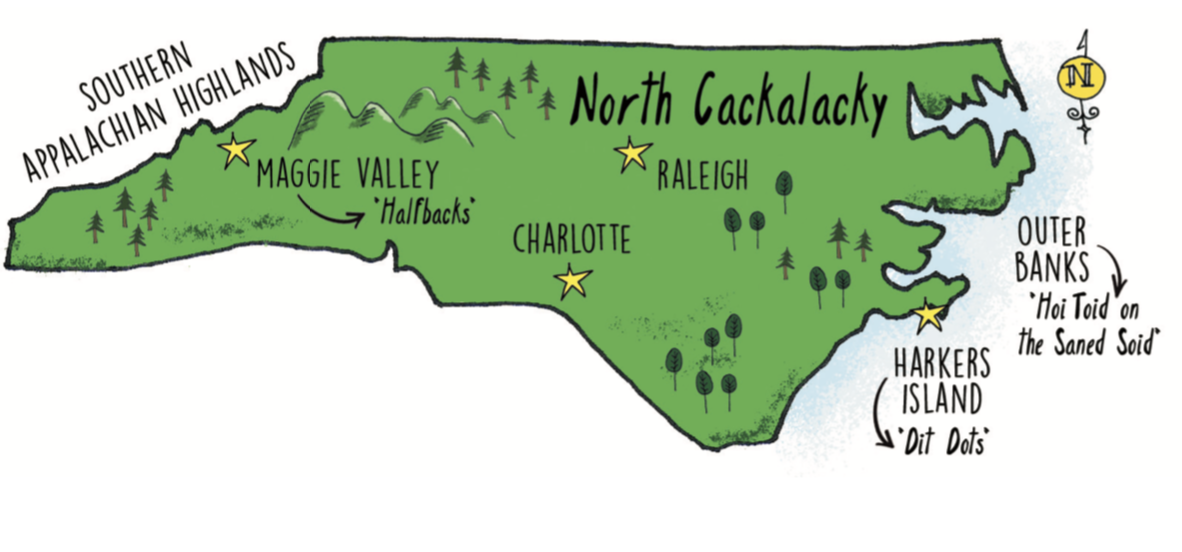

Wolfram’s subsequent research convinced him that North Carolina is the most linguistically diverse state in the country. As director of the university’s Language and Life Project, he identified five distinct dialect areas across the state: Pamlico Sound, North Carolina Coastal Plains, Virginia Piedmont, North Carolina Piedmont and Southern Appalachian Highlands.

Here’s a small sample of regional jargon that Wolfram has documented.

Hoi Toid on the Saned Soid

This phrase from the Pamlico Sound area would flabbergast anyone equating North Carolina with Appalachia. To outsiders, it sounds like a foreign language.

“Residents of the Outer Banks region are also known as hoi toiders because of the way they pronounce the long ‘I’ vowel,” Wolfram explains. “They pronounce high tide as hoi toid. And they have a distinct pronunciation of sound as saned. An often-said phrase from the region is ‘high tide on the sound side.’ But outsiders hear it as ‘hoi toid on the saned soid.’”

See more: Waxhaw’s Museum of the Alphabet Profiles Lingual History

Halfbacks, Dit Dots and Dingbatters

Consciously or not, we classify people according to whether or not they are part of our community. We sometimes invent names for people who don’t understand our way of life.

Appalachians have a term for Yankees vacationing in the mountains.

“In some parts, like in Maggie Valley, halfbacks refers to Northerners who go to Florida for the winter and in the summer go halfway back north, to the mountains of Appalachia, because it’s too hot in the South,” Wolfram says.

Residents of Harkers Island, in the Pamlico Sound region, call outsiders dit dots. The term came about because tourists couldn’t decipher the local dialect, as Wolfram explains. “So the locals responded, ‘What do you want us to do, talk in Morse code so you can understand us, like dit-dot, dit-dot, dot?’”

One Outer Banks term that might get more usage can be traced back to a particular year. “In 1972, the Outer Banks got television,” Wolfram says. “A hit show at the time was All in the Family. Archie Bunker, its main character, often called his wife a dingbat because, in his misogynist view, she didn’t have any common sense. People on the Outer Banks appropriated the term and started calling tourists dingbatters.”

North Cackalacky

Of course, tourists and other outsiders usually have their own, often derogatory, names for the locals. But over time, outsiders’ mocking terms sometimes lose their sting and gradually find their way into the vernacular as terms of endearment and even pride. Cackalacky is a prime example.

The term seems to have cropped up on military bases in remote areas throughout the state. Many soldiers stationed there were outsiders and naturally thought the natives sounded funny.

“Cackalacky started out as a mockery of the local accent,” Wolfram says. “But over time, North Carolinians appropriated it into a positive thing. Some older people still see North Cackalacky as an insult, while to younger people it’s a badge of pride.”

See more: 5 Reasons to Visit the North Carolina Transportation Museum

If our speech loses its distinctness, a big part of our community identity is erased. Wolfram believes we should cherish our local dialects, not discard them.

“Our whole point is that it’s part of Southern legacy,” he says. “North Carolina loves its literature, music and topography – but accompanying that is this rich legacy of dialects that should be celebrated just as we celebrate other parts of the state’s culture. That’s my mission.”

– Paul F. Brown

Yes you talent 🙂